High Bar vs. Low Bar Squats: Which is Right for You?

What's In This Article

- Key Highlights

- Introduction

- High-Bar and Low-Bar Squats

- Form Differences Between High-Bar and Low-Bar Squats

- Performance Differences and Similarities

- Benefits of Each Squat Type

- Practical Application

- Conclusion - High Bar Vs Low Bar Squat

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

- Resources

Key Highlights

- High-bar squats emphasize the quadriceps with an upright torso, while low-bar squats focus on posterior chain muscles with a forward lean.

- Barbell placement significantly affects muscle engagement, joint stress, and overall squat performance.

- High-bar squats are ideal for Olympic weightlifters and those seeking quadriceps development, low-bar squats benefit powerlifters.

- Both squat variations contribute to strength building and muscle hypertrophy through different muscle recruitment patterns.

- Choosing between these squats depends on individual goals, mobility, and specific athletic requirements.

Introduction

Squatting, a cornerstone in strength training regimes, commands universal respect for its unparalleled efficacy in building lower body strength and increasing muscle mass. With its myriad variations, this fundamental exercise enhances athletic performance and fortifies everyday functional movements. Among these variations, the high and low bar squats have emerged as focal discussion points and practice among strength training enthusiasts.

Greg Nuckols, a powerlifter and writer with Stronger by Science, explains that most people can squat more with a low bar than a high bar because it is easier on the back and requires more hip extension torque. This makes the low bar squat a preferred choice for powerlifting due to its ability to lift heavier weights.

Understanding their form and technique and the physiological and biomechanical underpinnings that define their role in strength and conditioning programs is imperative. This exploration offers insight into two of the most debated squat styles and a broader understanding of how specific variations in a fundamental exercise can lead to significant differences in training outcomes.

High-Bar and Low-Bar Squats

What is a High-Bar Squat?

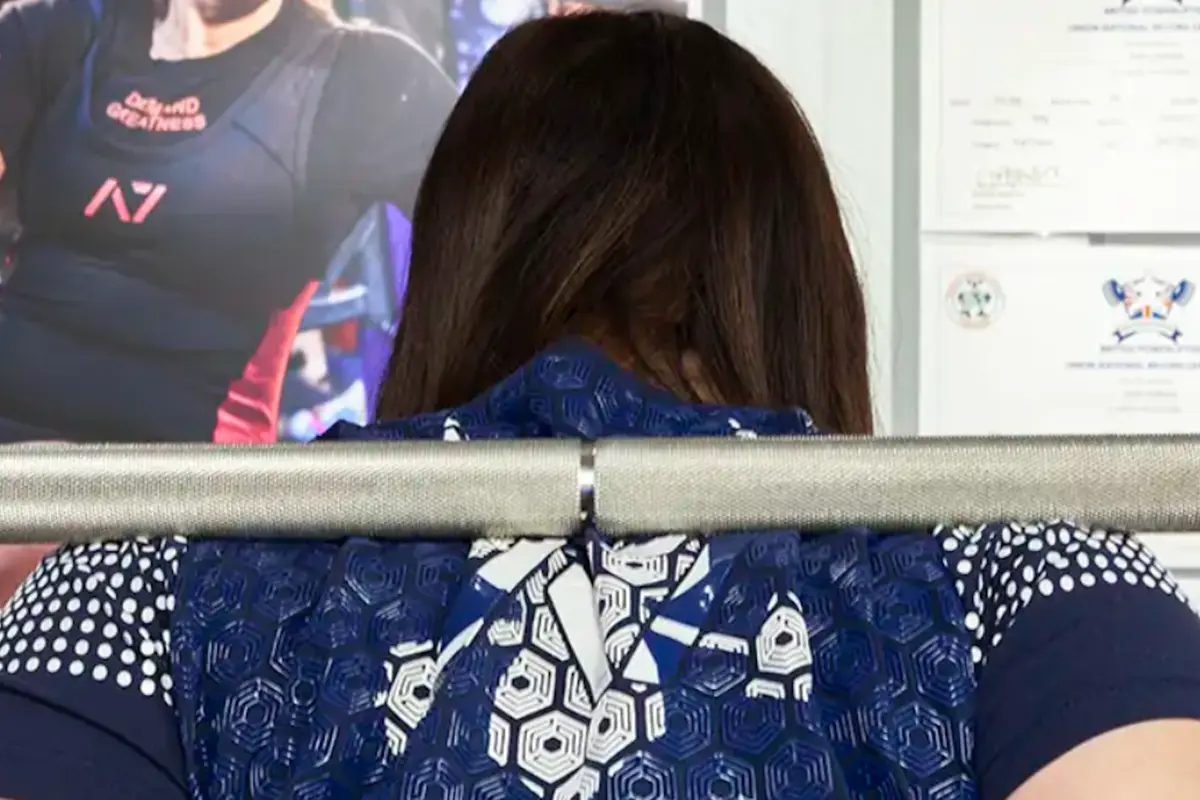

The high bar squat is a variant of the traditional barbell squat, distinguished by its specific bar placement and the resultant body mechanics. The barbell rests on the lifter's upper trapezius muscles, just below the neck, which necessitates a more upright torso to maintain balance. This upright position is crucial, as it aligns the bar over the mid-foot throughout the movement, ensuring a vertical path.

- This variation requires a lifter to maintain a chest upright posture, with the knees tracking over the toes, often moving past the knee joint. Good ankle mobility is also necessary.

- This position reduces stress on the lower back and emphasizes the quadriceps muscles and upper back.

- This style encourages a deep knee bend, vital for muscle activation in the thighs and glutes.

- Due to its demand for a strong, neutral spine and core stability, it is not just a lower-body exercise but also a full-body movement.

What is a Low-Bar Squat?

Conversely, the low bar squat position, often favored by powerlifters, involves positioning the barbell lower on the back, specifically on the rear deltoids or just below the shoulder blades. This position shifts the lifter's center of gravity backward, necessitating a more pronounced forward lean to keep the barbell aligned with the mid-foot.

- Thus, this position engages the posterior chain muscles—including the glutes, hamstrings, and lower back—more intensively than the high bar squat.

- The technique for a low bar squat also differs regarding limb positioning. It typically involves a wider stance than the high bar squat, with toes pointed slightly outward to accommodate the forward lean.

- This positioning also means less stress on the knee joint, as the angle of the torso reduces the knee extension moment.

- This squat is particularly effective for lifting heavy loads due to its biomechanical advantages, which include a shorter bar path and more efficient force transfer through the posterior chain.

- A 2021 study by Kristiansen et al. compared the SSB's kinematics, kinetics, and myoelectric activity with the high bar and low bar squat. It found that low-bar squats allowed greater loads to be lifted and more significant gluteus maximus activity in safety-bar squats.

Form Differences Between High-Bar and Low-Bar Squats

A 2017 study by Glassbrook et al. highlighted that high-bar back squats (HBBS) are characterized by greater knee flexion, lesser hip flexion, and a more upright torso, while low-bar back squats (LBBS) involve greater hip flexion and a more significant forward lean. LBBS emphasizes the posterior-chain hip musculature, while HBBS emphasizes the quadriceps.

The High-Bar Squat Technique

This squat technique is characterized by specific biomechanics that optimize the engagement of the quadriceps and core while maintaining a more upright torso. The key steps include:

- Barbell Positioning: The barbell is placed on the upper traps near the base of the neck. This position requires the lifter to have good shoulder mobility to comfortably rest it on the traps.

- Starting Position: The lifter stands with feet shoulder-width apart and toes slightly pointed out. This position aids in maintaining balance during the squat.

- Descent: The lifter breaks simultaneously at the knees and hips, maintaining an upright position in the chest. The knees track over the toes, and due to the high bar position, there is a significant degree of knee flexion.

- Depth: The goal is to achieve a deep squat with the hips dropping below the knee joint. Good ankle mobility facilitates this depth, allowing for greater dorsiflexion.

- Ascent: The lifter drives up through the heels, maintaining the upright torso and vertical bar path, activating the quadriceps and glutes to return to the starting position.

The Low-Bar Squat Technique

The low bar squat, while similar in its fundamental movement pattern to the high version, has distinct form characteristics catering to posterior chain activation:

- Barbell Positioning: The barbell rests lower on the back, on the rear deltoids, just below the shoulder blades. This position often requires less shoulder mobility than the high bar squat.

- Starting Position: The stance is usually wider than shoulder width, with toes pointed outwards to accommodate a more pronounced forward lean.

- Descent: The hips move back first, followed by a knee bend. The torso's forward lean is more significant than the high bar squat, aligning the barbell over the mid-foot.

- Depth: The depth of a low bar squat is typically to a point where the hips are just below parallel with the knee joint, focusing on posterior chain muscle activation without excessive knee flexion.

- Ascent: The lifter drives upwards through the heels, with the hips and shoulders rising simultaneously, emphasizing the engagement of the glutes and hamstrings.

Key Form Differences

The primary differences between the two squat styles lie in their barbell placement, body alignment, and muscle emphasis:

- Barbell Placement and Body Alignment: The high barbell position leads to a more upright torso and deeper knee flexion, while the low bar position causes a forward lean and focuses on hip hinging.

- Muscle Emphasis: High placement squats engage the quadriceps and upper back more intensely, whereas low bar squats emphasize the posterior chain, including the glutes, hamstrings, and lower back.

- Joint Stress: High bar squats place more stress on the knee joint due to increased knee flexion, while low bar squats can reduce knee stress but increase the load on the lower back.

- Mobility Requirements: High bar squats require good ankle and upper back mobility, whereas low bar squats demand less ankle mobility but more attention to hip and lower back flexibility.

Performance Differences and Similarities

Strength Building

Both variations are pivotal in building overall strength, but due to their unique biomechanics, they contribute in different ways. A 2019 study by Glassbrook et al. compared joint angle and ground reaction force differences between HBBS and LBBS above 90% 1RM. It suggested that LBBS is preferable for lifting the greatest load possible and emphasizes stronger hip musculature, while HBBS is more suited for movements with a more upright torso position.

- High Bar Squat: This variant primarily strengthens the quadriceps, glutes, and core muscles. The upright torso position and deeper knee flexion necessitate significant quadriceps engagement, thus contributing to enhanced leg strength. Moreover, maintaining the upright position under load also builds considerable core stability, a vital aspect of overall strength.

- Low Bar Squat: This variation, with its pronounced forward lean and emphasis on the posterior chain, more effectively targets the glutes, hamstrings, and lower back. This squat variation is especially beneficial for increasing the strength of the posterior chain, which is crucial for overall lifting ability. The ability to handle heavier weights in this position also translates to potential increases in overall strength.

Muscular Hypertrophy

Muscle growth, or hypertrophy, is influenced by muscle tension, damage, and metabolic stress. The two squat variations, by their different muscle recruitment patterns, contribute distinctly to hypertrophy.

- High Bar Squat: This variation emphasizes the quadriceps and requires significant knee extension, which is excellent for developing the front of the thighs. This squat style's full range of motion also contributes to substantial muscle activation and growth.

- Low Bar Squat: This variation's focus on the posterior chain makes it particularly effective for developing the glutes and hamstrings. Lifting more weight with this style can increase muscle tension and muscle mass in these areas.

Application to Training and Powerlifting

The application of either variation to other main lifts depends on the specific strength goals and the biomechanical requirements of those lifts.

Sebastian Padilla, Head of coaching education at SoCal Powerlifting, says that the high bar squat primarily engages the quadriceps to straighten the knees, which benefits those with strong quads and shorter femurs. In contrast, the low bar squat involves multiple muscle groups, including the quadriceps, glutes, hamstrings, and back erectors. It makes it more effective for general strength trainees and powerlifters due to its emphasis on the posterior chain.

- High Bar Squat: This squat style benefits athletes and lifters who engage in activities requiring an upright position and explosive leg power, such as Olympic weightlifting. The upright torso and quadriceps strength developed through this technique translates well to movements like the snatch and clean and jerk.

- Low Bar Squat: Powerlifters and those focused on increasing their lifting capacity often prefer this variation. The enhanced posterior chain strength and the ability to handle heavier loads directly benefit other major lifts like the deadlift.

Benefits of Each Squat Type

Benefits of a High-Bar Squat

- Improved Quadriceps Development: The vertical bar path and deeper knee flexion extensively activate the quadriceps, improving strength and muscle mass in the front thigh area.

- Mike Tuchscherer, a prominent figure in powerlifting, emphasizes the importance of high bar squats for developing quad strength and muscularity, which can sometimes be lacking in lifters who only perform low placement squats.

- Enhanced Core Stability: Maintaining balance in the upright position requires significant core engagement. This strengthens the abdominal and lower back muscles, contributing to overall core stability.

- Greater Depth and Flexibility: They allow for a deeper range of motion, improving lower body flexibility, particularly in the hips and ankles.

- Application in Olympic Weightlifting: The movement pattern and upright position closely mimic those in Olympic lifts, making it a valuable training exercise for Olympic weightlifters.

- Reduced Stress on the Lower Back: The upright torso position puts less strain on the lower back than the low bar squat, making it a preferable option for those with lower back issues.

Benefits of a Low-Bar Squat

- Increased Posterior Chain Strength: This position emphasizes the muscles of the posterior chain, including the glutes, hamstrings, and erector spinae, enhancing overall strength and muscle development in these areas.

- Potential for Heavier Lifts: The biomechanics allow lifters to typically handle more weight, contributing to more significant overall strength gains.

- Reduced Shear Stress on the Knee: The body's angle reduces the force exerted on the knee joint, which can benefit individuals with knee issues.

- Efficient for Powerlifting: The mechanics align well with the demands of powerlifting, making it a fundamental exercise for athletes in this sport.

- Improved Hip Mobility and Strength: The hip hinge movement effectively develops hip strength and mobility, which is essential for various athletic movements.

Each squat type, with its unique benefits, caters to different training needs and goals. Whether focusing on developing specific muscle groups, preventing or accommodating existing joint issues, or aligning with specific athletic disciplines, understanding these benefits is key to optimizing squat training.

Practical Application

When to Use High-Bar Squats

These squats are particularly advantageous in specific training scenarios and for certain goals:

- Olympic Weightlifting Preparation: Athletes focused on Olympic lifts should incorporate this variation due to its similar movement pattern and upright torso requirement.

- Quadriceps Development: The high bar squat's emphasis on this muscle group makes it ideal for individuals aiming to specifically strengthen and build the quadriceps.

- Enhancing Core and Upper Body Stability: This variation benefits those looking to improve their overall core and upper body stability, as the upright position demands significant engagement of these areas.

- Athletes with Good Ankle Mobility: This variation allows athletes with good ankle mobility to benefit from the deeper squat position.

- Individuals with Lower Back Sensitivity: The upright position places less stress on the lower back, making it a suitable option for those with

When to Use Low-Bar Squats

These squats are more appropriate in different scenarios:

- Powerlifting Training: Given the ability to handle more weight, this variation is ideal for powerlifters or those focused on increasing their overall lifting capacity.

- Posterior Chain Development: This variant is highly effective for athletes who want to strengthen their glutes, hamstrings, and lower back.

- Individuals with Limited Ankle Mobility: The forward lean reduces the demand for ankle mobility, making it a good option for those with restricted ankle movement.

- Knee Sensitivity: The reduced knee flexion can benefit lifters with knee issues, as it places less stress on the knee joint.

How to Program Each Squat in Your Routine

Incorporating both squats into a training regimen requires consideration of individual goals, mobility, and existing strengths. Juggernaut Training Systems head coaches and JuggLife podcast hosts Chad Wesley Smith and Max Aita suggest alternating between the two variations, especially for those experiencing shoulder or elbow pain with low-bar squats.

- Balance Training Goals with Variations: Include both styles to achieve a balanced development of the quadriceps and the posterior chain.

- Periodization: Rotate between high and low barbell placements in different training cycles to maximize overall development and prevent overuse injuries.

- Volume and Intensity Adjustments: Adjust volume and intensity based on the variation. For example, high placement may require a higher volume with moderate weights to maximize quadriceps engagement, while the low variation can be done with heavier weights but lower volume.

- Technical Proficiency: Focus on mastering the technique of each squat style before increasing the weight, as proper form is crucial for effectiveness and injury prevention.

Conclusion - High Bar Vs Low Bar Squat

Exploring these two variations reveals distinct technical aspects, benefits, and applications for all fitness levels. High-placement squats target the quadriceps with an upright torso, while low-placement squats emphasize the posterior chain for overall strength, which is ideal for powerlifting. Both styles contribute to strength, muscle growth, and athletic performance based on goals and capabilities. Incorporating both styles in training leads to well-rounded strength and muscle development.

Which One is Better?

Choosing the best squat variation depends on individual goals, conditioning, and mobility.

Natalie Smith, a Strength/Powerlifting coach, NASM-CPT and USPA Certified Powerlifting Coach-Practitioner, highlights that high bar squats are excellent for beginners and Olympic weightlifters due to their more upright posture and greater range of motion. He contrasts this with low bar squats, which are more technical and allow lifters to squat 10-15% more weight, making them the preferred choice for competitive powerlifters.

Select the squat style based on your training needs, goals, and biomechanics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need special mobility to perform these squat variations?

Each variation requires different mobility. High-bar squats demand good ankle and upper back mobility for an upright posture. In contrast, low-placement squats require more hip and lower back flexibility and are more forgiving for those with limited ankle mobility.

Can I incorporate both squat types in my training?

Absolutely. Rotating between both squat styles can provide balanced muscle development, prevent overuse injuries, and help target different muscle groups. Many athletes use periodization to alternate between these variations.

Which squat is better for building muscle?

Both variations can contribute to muscle hypertrophy but target different muscle groups. High-placement squats are excellent for developing the quadriceps, while low are more effective for building the glutes and hamstrings.

Which squats are safer for people with existing joint issues?

Safety depends on individual biomechanics and specific joint concerns. High-bar squats typically place less stress on the lower back due to the upright torso, while low can reduce knee joint stress by minimizing knee flexion. Each variation is potentially better for different types of joint sensitivities.

References

- Glassbrook, D. J., Brown, S. R., Helms, E. R., Duncan, S., & Storey, A. G. (2019). The High-Bar and Low-Bar Back-Squats: A Biomechanical Analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33(Suppl 1), S1-S18.

- Glassbrook, D. J., Helms, E. R., Brown, S. R., & Storey, A. G. (2017). A Review of the Biomechanical Differences Between the High-Bar and Low-Bar Back-Squat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(9), 2618-2634.

- Kristiansen, E., Larsen, S., Haugen, M. E., Helms, E., & van den Tillaar, R. (2021). A Biomechanical Comparison of the Safety-Bar, High-Bar and Low-Bar Squat around the Sticking Region among Recreationally Resistance-Trained Men and Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8351

Resources

- BarBend: Master the Low Bar Back Squat for High-Level Leg Gains

- SoCal Powerlifting: High bar vs Low bar Squats

- BarBend: The Differences Between High-Bar Vs. Low-Bar Squats Explained

- Healthline: High Bar vs. Low Bar Squat: What's More Effective?

- YouTube: High Bar Squat vs. Low Bar Squat by Alan Thrall