Squat Strength at the Bottom: Top Training Strategies

What's In This Article

- Key Highlights

- Introduction

- Mechanics of the Squat

- First Steps for Addressing Strength in the Bottom Position

- Strength Building Exercises for Power out of the Hole

- Advanced Techniques for Strength out of the Hole

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

- Resources

Key Highlights

- Success in squatting requires mastering the "hole" position - the lowest point where hips drop below knees - as it's often the most challenging part of the lift.

- Proper squat mechanics involve coordinated movement of the quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and core muscles and correct hip, knee, and ankle positioning.

- Video analysis is crucial for identifying form issues and tracking progress in squat technique development.

- Pause squats and pin squats are essential variations for building strength specifically in the bottom position of the squat.

- Programming should include a mix of heavy main lifts, technique work, and accessory exercises spread across multiple weekly sessions.

- Advanced techniques like eccentric training and using chains or bands can help develop explosive power out of the bottom position.

Introduction

A strong squat requires skill, especially coming up from the lowest part, also known as coming "out of the hole." This phase, reflecting the ascending strength curve, challenges athletes and is key to progressing in lifting heavier weights.

Chad Wesley Smith, a respected strength coach and owner of Juggernaut Training, emphasizes that the hole is crucial for raw squatters. He states that it's impossible to be a great squatter without strength out of the hole, and being explosive in this portion of the lift helps overcome sticking points.

As a powerlifting coach at Sportive Tricks Strength, I've seen firsthand that building a big squat takes more than grinding through heavy sets. Through years of helping athletes break through plateaus, I've learned that magic happens when we combine precise technical work, targeted accessory movements, and intelligent programming to build great technique.

In this post, I'll share my approach to developing explosive power out of the hole, without replacing the place of regular squats. Whether you're struggling with getting stuck at the bottom or just looking to add serious weight to your squat, I'll break down the strategies that have consistently worked for my athletes.

Mechanics of the Squat

The squat is a compound exercise that activates a range of muscles throughout the body:

- The quadriceps, hamstrings, gluteus maximus, and erector spinae.

- Support muscles such as the core and lower back to help with stability and posture during the lift.

The biomechanics of squatting entail an interaction of joint movements, including:

- Hip and knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion

- These actions collaborate to lower and lift the body.

- Successfully performing this lift relies on the strength and coordination of these muscles, along with the lifter's capacity to maintain an even weight distribution.

The Significance of the "Hole"

The "hole" refers to the lowest position of the squat, where the hips drop below the knees. This position is often the key point of the squat's difficulty due to several factors:

- The mechanical disadvantage of this position

- The diminished contribution of the stretch reflex

- The increased demand for muscular control and stability.

A 2021 study by Larsen et al. analyzed the sticking region in back squats using 3-RM loads. The sticking region was identified as occurring between 0 and 15 cm from the lowest vertical barbell point. During this phase, ground reaction force output decreased, and hip moment arms increased while knee moment arms decreased. This created a biomechanically disadvantageous position for force generation, particularly for the quadriceps and soleus muscles, which showed reduced myoelectric activity.

Emerging from the hole requires muscular strength and high proprioceptive skills to engage the right muscles at the right time, which is essential for great squatters.

Common Challenges

Lifters can encounter many challenges when squatting, particularly ascending out of the hole.

- Mobility restrictions, notably in the ankles and hips, can make it hard to achieve full depth while maintaining proper form. This limitation often leads to compensatory mechanisms, for example, excessive forward lean or valgus collapse of the knees, which can increase the risk of injury and diminish the effectiveness of the lift.

- A lack of core stability may cause a failure to maintain an upright torso, complicating the ascent.

- Technique errors, such as improper breathing and bracing, incorrect foot placement, and a lack of consistency in depth, also contribute to difficulties in building strength from the bottom position.

A 2024 study by Staub and Powers shows that trunk and tibia angles significantly influence joint loading during the sticking point. Forward trunk lean increases hip extensor demand while reducing knee extensor contribution. This interplay can exacerbate difficulty during the sticking phase if not correctly managed.

Assessing Your Weakness

- Identifying weak points in the squat requires self-assessment and consultation with a powerlifting coach, if available.

- Video analysis can help pinpoint form deviations such as inadequate depth or improper knee alignment, revealing underlying strength or mobility issues.

- A coach can provide feedback for improvement.

In their comprehensive 2016 paper, Kompf and Arandjelovic state that understanding the mechanics of this sticking point can inform:

- Analyzing athletic performance

- Designing targeted training strategies to overcome sticking points

- Preventing potential injuries at these biomechanically challenging positions

Mobility and flexibility are key to optimizing squat depth for improved strength and power.

- Ankle and hip restrictions can impact form, leading to shallow squats and reduced force.

- Tightness in the thoracic spine or hip flexors can affect torso posture and squat performance.

Targeted stretching and mobility exercises are crucial for enhancing squat depth and building strength.

First Steps for Addressing Strength in the Bottom Position

Proper Squat Form

See our step-by-step technique guide for a detailed breakdown of how to squat.

- Stand with feet shoulder-width apart and toes slightly pointed outward to allow natural hip movement.

- Position the barbell correctly. For back squats, secure across the upper back. For front squats, rest against the front shoulders.

- Brace your entire core.

- Begin the descent by pushing your hips back and down while keeping your chest upright to maintain proper spine alignment.

- Keep your knees tracking over your toes as you lower.

- Lower until hips drop below knee level to achieve full depth and maximize muscle engagement.

- Drive back up by pressing through your whole foot, engaging quads, hamstrings, and glutes until you return to the starting position.

Strength Coach Josh Bryant, who learned from powerlifting legend Eddy Coan, emphasizes the importance of consistent technique. He notes that great squatters like the late Dr. Fred Hatfield and Eddy Coan descend with the same speed and to the same depth every time. This consistency allows for optimal utilization of the stretch reflex, which is crucial for power out of the hole.

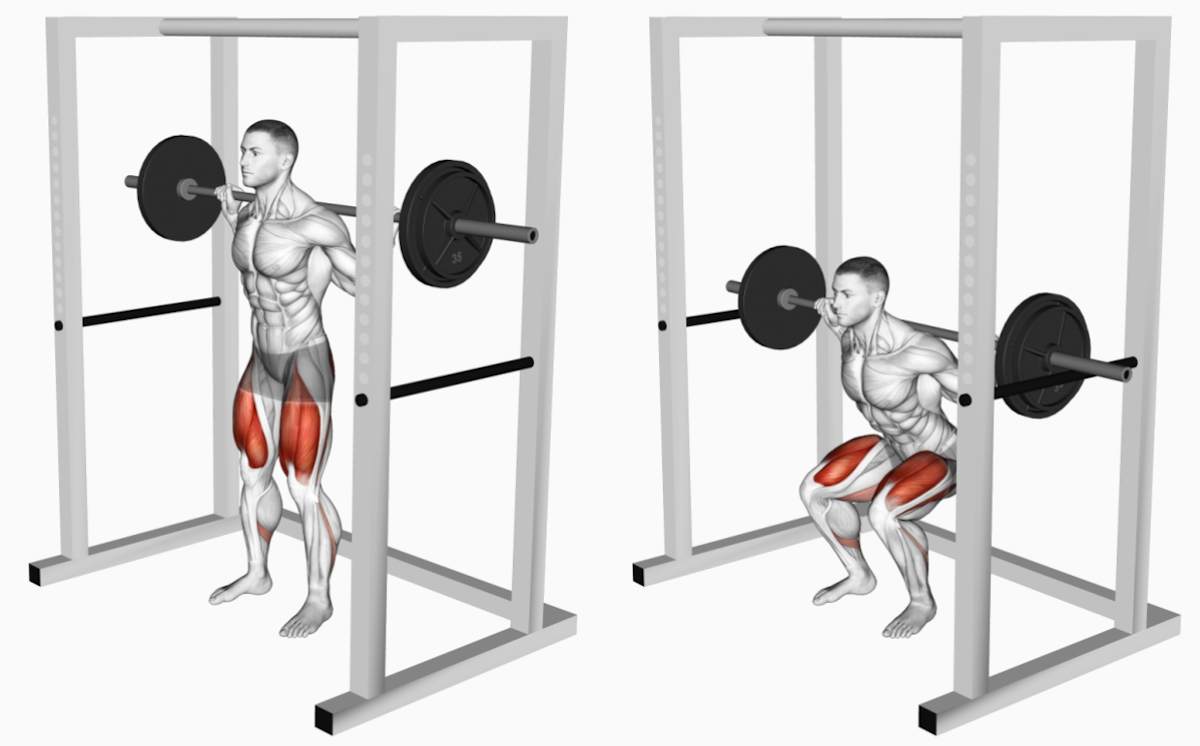

##VIDEO##

Adjustments for Strength Out of the Hole

Power from the bottom of the movement can be achieved through strategic adjustments in technique.

- Widening the stance slightly beyond shoulder width allows for a greater range of motion. It can increase the engagement of the glutes and hamstrings, muscles needed for driving upwards from the hole. (Escamilla et al., 2001).

- Adjusting the foot angle slightly more outward can help to accommodate hip mobility, allowing for deeper squats without compromising form.

These modifications must be to the lifter's biomechanics and can significantly impact the ability to generate force in the concentric portion of the squat, particularly from the deepest point.

Video Analysis

Video analysis can help improve squat technique.

- It gives visual feedback from different angles, highlighting strengths and areas to work on.

- This method allows a close look at each movement phase, from start to finish.

- The focus is on transition points where mistakes show up.

- Athletes can monitor their progress through regular video checks, tweaking their technique gradually.

Strength Building Exercises for Power out of the Hole

To build strength directly from the hole, specific exercises that simulate the demands of this movement phase are paramount. Pause and pin squats stand out as beneficial variations and are endorsed by coaches like Wesley Smith.

Research conducted by Martinez-Cava and colleagues in 2021 examined two squatting methods over 10 weeks of training. One group performed squats with a 2-second pause at the bottom position between the lowering and lifting phases, while the other group used continuous motion. The findings indicated that participants who incorporated the pause demonstrated superior improvements in neuromuscular function compared to those using the constant technique.

- This variation involves a deliberate pause at the bottom position for a count of two to three seconds before ascending.

- The cessation of movement eradicates the stretch reflex, forcing the muscles to generate as much force as possible without the initial momentum.

- This exercise strengthens the muscles and enhances the lifter's ability to maintain tension and stability under load.

- By initially performing pause squats with a lighter weight, lifters can focus on form and gradually add heavy weights as their strength improves, building muscular and explosive power from the hole.

Pin Squats:

- Set up in a squat rack with safety pins at the lowest position of your squat so you start from the bottom end of the movement.

- Pin squats begin from a dead stop with the bar resting on the pins.

- This starting position forces the lifter to initiate the movement without the benefit of descending momentum, closely mirroring the demand of driving out of the hole.

- Pin squats emphasize the concentric portion of the lift, building explosive strength crucial for overcoming sticking points.

Leg Press:

- While not a direct squat variation, the leg press machine allows lifters to focus on strengthening the quadriceps and glutes with a heavier weight than they might manage in a squat.

- This exercise can be particularly beneficial for lifters looking to increase their leg power and improve their ability to push through the bottom of the squat.

Box Squats:

- By setting a box or bench at the desired depth, box squats train the lifter to reach a consistent depth with each repetition.

- The momentary pause on the box eliminates the stretch reflex, similar to pause squats, requiring the lifter to generate force from a complete stop.

- Adjusting the box height to just below parallel can help lifters target the specific range of motion needed for strength out of the hole.

Programming Examples

A sample workout routine might include:

- Monday: Squat Focus Day

- Main Lift: Back Squat - 5 sets of 5 reps working weights at 75% of 1RM

- Secondary Exercise: Paused Squats - 4 sets of 3 reps at 60% of 1RM, focusing on a 3-second pause at the bottom

- Accessory Work: Leg Press - 3 sets of 8-10 reps, emphasising full depth and controlled movement

- Wednesday: Recovery Day

- Light Cardio and Mobility Work: Focus on hip and ankle mobility exercises to improve squat depth and flexibility

- Friday: Explosive and Technique Day

- Main Lift: Pin Squats - 5 sets of 3 reps at 70% of 1RM, starting from the bottom position

- Accessory Exercise: Box Squats - 4 sets of 4 reps at 65% of 1RM, using a box height that mimics the lifter's squat depth

Volume, intensity, and exercise selection should be adjusted based on the lifter's progress, fitness level, and specific weaknesses.

Advanced Techniques for Strength out of the Hole

Eccentric Training

Incorporating eccentric-focused training into a squat regimen offers significant benefits, particularly for enhancing strength out of the hole.

- The eccentric phase, or the controlled lowering phase of the squat, involves lengthening the muscle under tension, leading to more significant increases in muscular strength and hypertrophy compared to concentric (lifting) movements alone.

- By training this phase—such as increasing the time taken to lower into the bottom of the squat (different descent speed) or using heavier weights during the descent (while safely controlling the weight with assistance or within a squat rack)—lifters can improve their muscle's ability to absorb and generate force.

- This increased force-generating capacity is crucial for transitioning powerfully out of the bottom position of the squat, thereby overcoming one of the most challenging aspects of the lift.

Overload Training

Overload training, employing methods like chains or bands, introduces variable resistance throughout the squat movement, making the lift progressively harder as one ascends.

- When attached to the barbell, chains or bands increase the resistance during the squat's concentric phase (standing up phase) as the weight of the chain lifts off the ground or the band's tension rises.

- This technique effectively trains the lifter to exert more force as they rise out of the hole, closely simulating the increasing difficulty of rising from the bottom position. The lowering phase feels like there isn't as much weight as you reach the bottom.

- The added resistance towards the top of the movement encourages lifters to push through their sticking points with greater explosive power, thereby enhancing overall squat performance.

Conclusion

Throughout this article, we've explored the comprehensive process of improving barbell squat strength. Techniques like optimizing form and incorporating compound movements and specific strength exercises and techniques are crucial. It's recommended to incorporate these strategies, track progress, and consider personalized coaching for better results for building heavy squats.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should I pause during pause squats?

Hold the bottom position for 2-3 seconds to eliminate the stretch reflex and build strength in the hole.

Is it normal to feel weaker at the bottom of a squat?

Yes - the bottom position creates a mechanical disadvantage, which is why specific training for this position is so necessary.

How wide should my squat stance be?

Start with your feet shoulder-width apart, then adjust them slightly wider or narrower based on your body proportions and mobility.

How can I improve my ankle mobility for better squat depth?

Regular ankle stretching, calf foam rolling, and practicing weighted ankle dorsiflexion drills can improve mobility over time.

Should I squat below parallel?

Yes, squatting below parallel (hips below knees) ensures full muscle engagement and better strength development, provided you can maintain proper form.

References

- Escamilla, R. F., Fleisig, G. S., Lowry, T. M., Barrentine, S. W., & Andrews, J. R. (2001). A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of the squat during varying stance widths. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33(6), 984-998.

- Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2017). The sticking point in the bench press, the squat, and the deadlift: Similarities and differences, and their significance for research and practice. Sports Medicine, 47(4), 631-640.

- Larsen, S., Kristiansen, E., & van den Tillaar, R. (2021). New insights about the sticking region in back squats: An analysis of kinematics, kinetics, and myoelectric activity. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 691459.

- Martínez-Cava, A., Hernández-Belmonte, A., Courel-Ibáñez, J., Conesa-Ros, E., Morán-Navarro, R., & Pallarés, J. G. (2021). Effect of pause versus rebound techniques on neuromuscular and functional performance after a prolonged velocity-based training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 16(7), 927-933.

- Straub, R. K., & Powers, C. M. (2024). A biomechanical review of the squat exercise: Implications for clinical practice. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 19(4), 490-501.